New research shows that Saskatchewan plant extracts, like dandelion, bergamot, and gaillardia, can help to stop MRSA growth.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, better known as MRSA, is a serious threat in Canadian health-care settings. This antibiotic-resistant bacterium spreads through direct contact and thrives in places like hospitals and long-term care facilities, where people are already vulnerable.

According to the Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System, MRSA is a leading cause of health-care-associated infections in Canada. It’s notorious for causing persistent wound infections and, in more serious cases, life-threatening bloodstream infections. What makes MRSA especially dangerous is its resistance to many antibiotics, which limits treatment options.

MRSA doesn’t affect everyone equally. Indigenous communities across Canada experience higher rates of these infections—reflecting broader health inequities rooted in colonialism and systemic barriers to care.

At the same time, Indigenous medicinal knowledge has deep roots, but has often been overlooked or undervalued by Western medicine.

"These plants have been used by Indigenous Peoples for thousands of years to treat serious illnesses and other ailments."

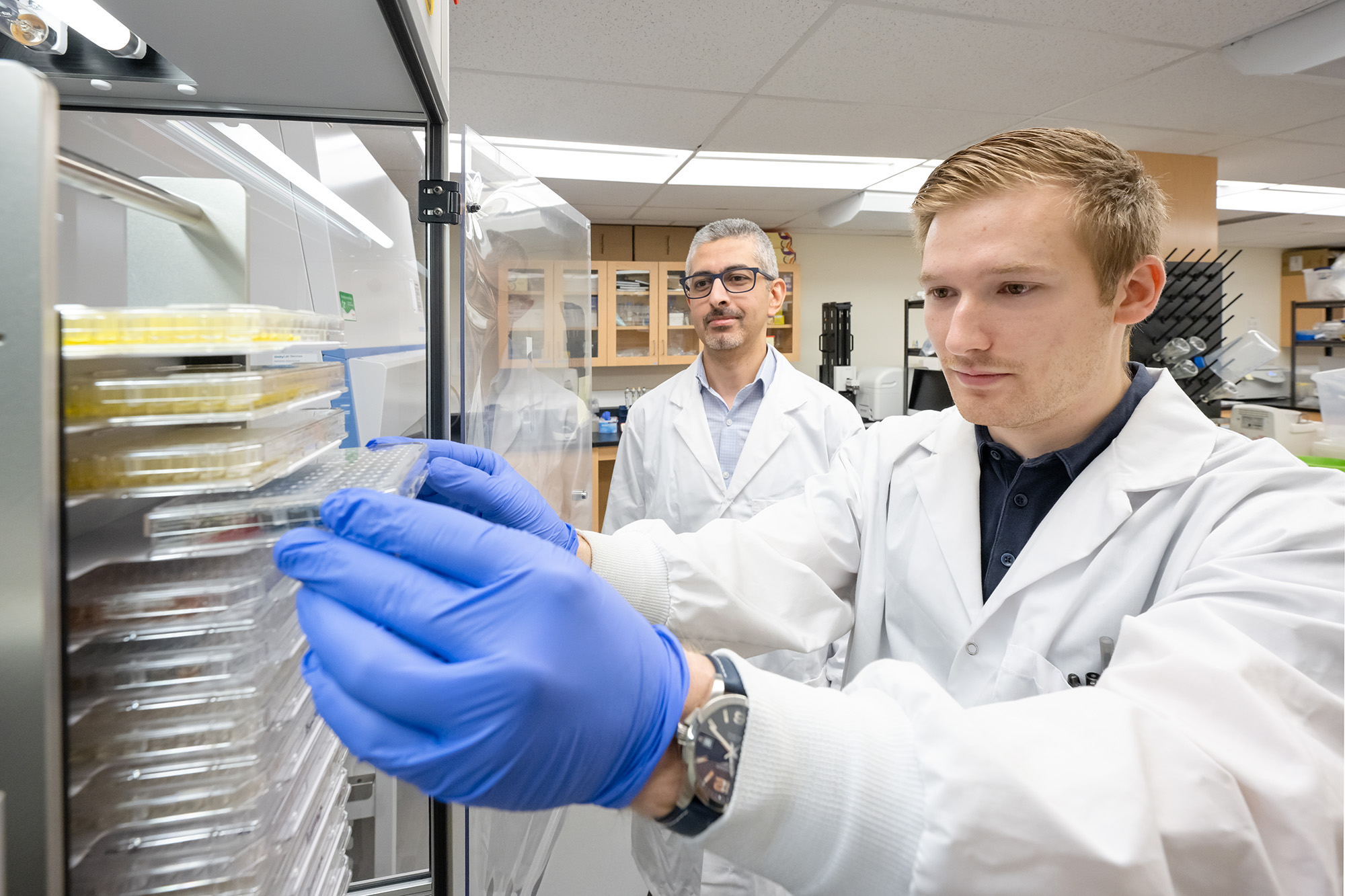

With antibiotic resistance on the rise and few new drugs in development, researchers at the University of Regina partnered with researchers and Elders at the First Nations University of Canada to explore a different approach: Can Indigenous medicinal plants help fight MRSA?

Together, they collected plant extracts from across the Canadian Prairies and tested them under lab conditions that closely mimicked real infections, not just standard petri-dish experiments.

The results were promising.

Prairie plants show potential

Several plant extracts—including bergamot, dock, gaillardia, and dandelion—were able to stop MRSA growth.

Other plants, like gumweed, helped break down biofilms—the protective layers bacteria form to shield themselves from antibiotics and immune responses. Biofilms make infections harder to treat and more likely to return, so breaking them down is a significant step forward.

Interestingly, some extracts—like those from chokecherry, hoary puccoon, and Northern bedstraw—only worked under infection-like conditions. This highlights the importance of realistic testing environments when exploring new treatments.

Perhaps most excitingly, the study found these plant extracts may work differently than existing antibiotics, opening new possibilities for tackling drug-resistant infections.

“The plants talk to you—you just have to listen. We always have our remedies carried with us. Once you learn it, you always know.”

Dr. Vincent Ziffle, associate professor of Indigenous Knowledge and Science at First Nations University of Canada, says the findings are not surprising.

“These plants have been used by Indigenous Peoples for thousands of years to treat serious illnesses and other ailments. What may be shocking is how this is often new information to others in the scientific community. We hope that our research—and the way we conducted it—helps conventional scientists begin working with Indigenous Knowledge Keepers, scientists, and communities in a good way. We are still learning and hope to do better as the relationships grow and research protocols are improved.”

Centering Indigenous leadership in health research

The study was led by Dr. Omar El-Halfawy, a Canada Research Chair in Chemogenomics and Antimicrobial Research at the University of Regina. He says the collaboration is as important as the findings.

“Our team recognises that MRSA is an Indigenous health priority, and through this project, we aimed to find ways to combat antibiotic resistance while supporting reconciliation efforts,” says El-Halfawy.

The research was recently published in Microbiology Spectrum, an open-access journal in microbial sciences.

Unlike many past studies where Indigenous Peoples were involved only as participants, this paper credited Indigenous Elders and non-Indigenous researchers equally, setting a new standard for collaborative, respectful, and reciprocal research.

“Sadly, three Elders who collaborated on this work passed away before our paper was published. We’re deeply grateful they entrusted us with their traditional knowledge and medicinal plants. This study is a way to honour their contributions and carry their legacy and wisdom forward,” El-Halfawy says.

Ziffle says it was meaningful to spend time with Elders and students in their home communities and throughout Saskatchewan’s prairies, boreal plains, and forests.

“It was illuminating and clearly lifted students’ spirits to see where Indigenous science is best demonstrated and where it comes from," says Ziffle.

Elder Margaret Reynolds, who was part of the projects, says, “Our medicines came from Mother Nature. Now these students know about the importance of medicinal plants by being on and learning from the land.”

A blueprint for the future

This study highlights both the untapped potential of Indigenous plant medicines and how research can be done in ways that honour traditional knowledge and support Indigenous health leadership.

El-Halfawy says the collaboration could serve as a blueprint for future projects, bringing together diverse ways of knowing to address urgent health challenges.

Elder Florence Allen, who was also part of the research team and has recently passed away, said, “The plants talk to you—you just have to listen. We always have our remedies carried with us. Once you learn it, you always know.”